Most hydroponic systems fall into one of two broad categories: passive and active. Passive systems, such as reservoir or wick setups, depend on the molecular action inherent in the wick or in the medium to make water available to the plant. Active systems, which include the flood, recirculating drip, and aerated water systems, use a pump to send nourishment to the plant.

Most commercially made “hobby” hydroponic systems designed for general use are built shallow and wide, so that an intensive garden with a variety of plants can be grown. However, most marijuana growers prefer to grow each plant in an individual container. Indoors, a three-gallon container is adequate. Outdoors, a five-gallon (or larger) container should be used if the water cannot be replenished frequently. Automatic systems irrigated on a regular schedule can use smaller containers, but all containers should be deep, rather than shallow, so that the roots can firmly anchor the plant.

PASSIVE HYDROPONIC SYSTEMS

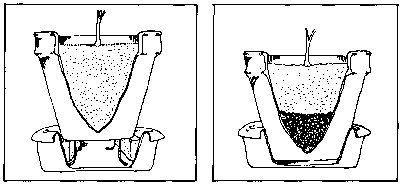

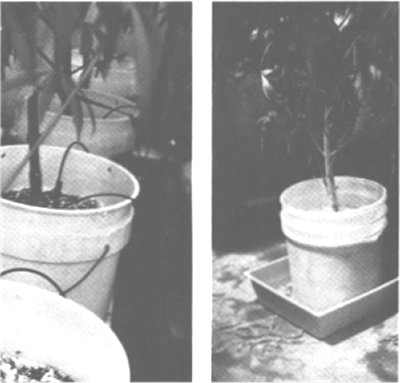

The wick system is inexpensive and easy to set up and maintain. The principle underlying this type of passive system is that a length of 3/8 to 5/8 inch thick braided nylon rope, used as a wick, will draw enough nourishment from a reservoir filled with a water/nutrient solution to keep a growing medium moist. The container, which holds a rooting medium, has wicks running along the bottom and dropping through small, tight-fitting holes to the reservoir. Keeping the holes small makes it difficult for roots to penetrate to the reservoir. By increasing the number or length of the wicks, or their thickness, you can increase the amount of water delivered to the medium. A three-gallon container should have two wicks; a five-gallon container, three wicks. The wick system is self-regulating: the amount of water delivered depends on the amount lost through evaporation or transpiration.

Each medium has a maximum saturation level. Beyond that point, an increase in the number of wicks will not increase the level of moisture. A 1—1—1 combination of vermiculite, perlite, and Styrofoam makes a convenient medium, because the components are lightweight and readily available. Vermiculite alone sometimes develops too air-free an environment and becomes compacted, so that a tall plant might tip over. Perlite, which doesn’t compress, keeps the medium loose and airy. Styrofoam beads hold no water, and therefore help keep the medium drier. Pea-sized chopped polyurethane foam, gravel, sand, and lava can also be used to make a medium. In any case, the bottom inch of the container should be filled only with vermiculite, which is very absorbent, so that the wicks have a good medium for moisture transfer.

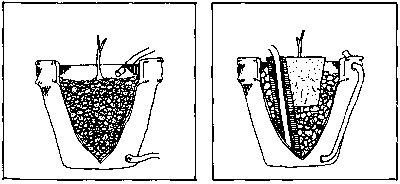

A wick system can be constructed as follows: Cut four holes, about ½”in diameter, in the bottom of a three-gallon container. Run the wicks through the holes so that each end extends about three inches outside the container. Unbraid the wicks to aid absorption. Put two bricks in the bottom of a deep tray (an oil drip pan will do fine), into which you’ve poured the water/nutrient solution, then place the container on the bricks so that the wicks are immersed in the solution. Keep replacing the solution as it is absorbed.

A variation on this system can be constructed by using an additional outer container rather than a tray. With this method, less water is lost through evaporation. To make sure that the containers fit together and come apart easily, place the bricks in the bottom of the outer container. Fill the outer container with the water/nutrient solution until it comes to just below the bottom of the inner container.

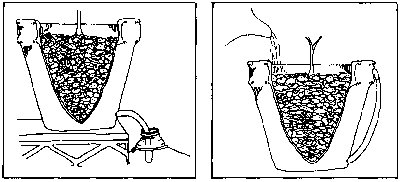

The reservoir system is even simpler than the wick system. For this setup you need only fill the bottom two or three inches of a 12-inch-deep container with a coarse, porous, inert medium such as lava, ceramic beads, or chopped pottery, and then pour in the nutrient/water solution. Variations on this method include a plastic flower pot or plastic growing bag sitting directly in a tray or pail of the nutrient/water solution.